Everyday laser flashes and real-world attosecond physics

Down in the basement of the Department of Physics, the now world-famous short laser pulses are fired almost daily. This is home to Sweden’s cutting-edge research in attosecond physics. According to Per Eng-Johnsson, professor in atomic, molecular and optical physics at the Faculty of Engineering (LTH), the research field is currently in the midst of a paradigm shift.

Sara Hängsel – Published 8 December 2023

The term “DIY” may appear to be an unlikely description of a high-tech laser laboratory used by a Nobel Prize-winning scientist. Yet this is the word Per Eng-Johnsson chooses to describe some aspects of the laser systems used by the 25 researchers and doctoral students at Lund University when investigating the world with attosecond pulses.

“We have built and developed parts of our best laser systems ourselves. Historically, researchers in attosecond physics have also been instrument developers to some extent. We have developed large parts of the required laser systems ourselves and, over time, adapted them according to our needs and wants. The reason is simple: it was impossible to buy this type of research equipment. It is only now, in recent years, that commercial equipment has started to catch up with research,” says Per Eng-Johnsson.

Indeed, as the equipment has been developed in research laboratories, it has also been partially commercialised.

“This has allowed researchers to shift their focus from developing the lasers themselves to being able to use them in experiments.”

"We now have one of the best terawatt lasers in the world"

Coincidentally, the University’s newest and most advanced laser system for attosecond pulse research is about to be inaugurated amidst the Nobel frenzy. The system, which is expected to be in use for decades to come, is currently being tested. It replaces the much-publicised but recently dismantled terawatt laser that first attracted Anne L’Huillier to Lund in the early 1990s.

“From time to time, commercial technology catches up with research. This is where we are now. The laser purchased in 1992 was cutting-edge and unique for its time. We now have one of the best terawatt lasers in the world. It’s a paradigm shift,” says Per Eng-Johnsson.

Sweden has three facilities for high-intensity laser systems. Lund University’s facility is the largest of them. Researchers from all over the world come to Fysicum via various networks to use the equipment.

A certain shift towards real-world applications

“This is not something one single research team can do on its own. It requires enormous basic infrastructure, well-functioning technical support and a large surrounding network of different collaborations.”

Per Eng-Johnsson’s own research focuses on ultrafast attosecond pulses. He is currently leading a collaboration between three research groups that received SEK 25 million in 2019 for a project on how to combine two different techniques for attosecond pulses. At present, LTH researchers use both techniques, but not simultaneously.

As research techniques mature and are refined, there is also a certain shift towards real-world applications. Although this is something that lies in the future, it has already started opening doors to opportunities and fields where this knowledge could play a major role.

“Our main focus is to conduct basic research on the subject through experiments that help us understand the properties of matter. When it comes to potential applications on the horizon, I primarily think of theoretical knowledge that could form the basis for different measurement methods. These methods could, in turn, serve as tools for e.g. the development of materials for solar cells and semiconductors.”

The reality of attosecond physics – see the research step by step

Nedjma Ouahioune and Ann-Kathrin Raab, who are both doctoral students, demonstrate how the facility’s smallest laser system works. Photo: Charlotte Carlberg Bärg

The reality of attosecond physics

Step into LTH's high-tech laser laboratory and observe the everyday reality of attosecond physics.

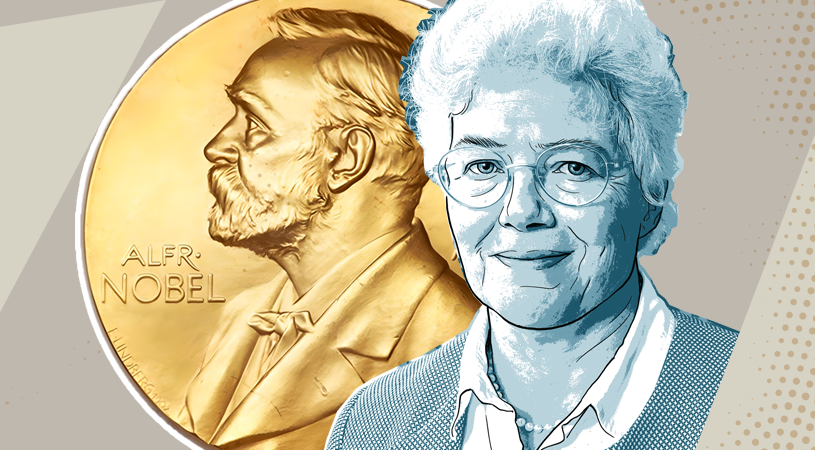

The Nobel Prize in Physics 2023

Professor Anne L’Huillier, Atomic Physics at LTH, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2023, jointly with Pierre Agostini and Ferenc Krausz, for their experiments, which have given humanity new tools for exploring the world of electrons inside atoms and molecules.